What happened to our summit push?

In short:

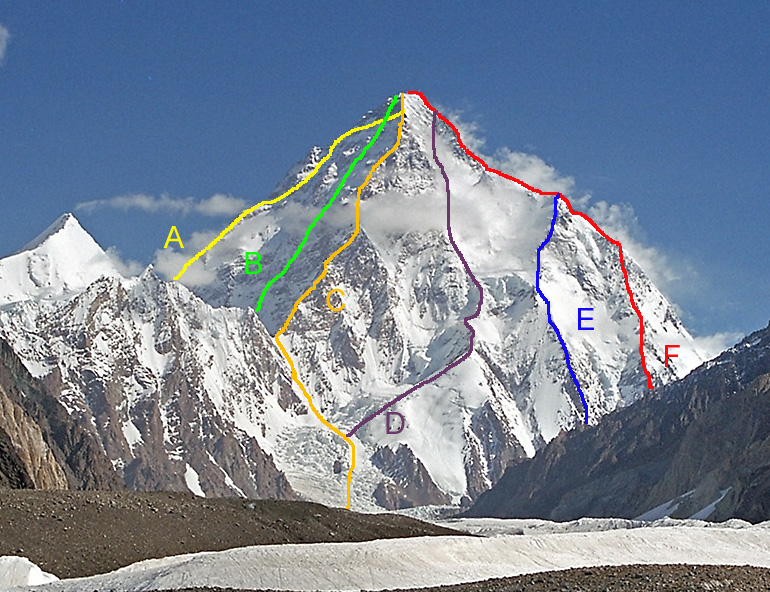

We started yesterday night (of 17 July) at 8 pm from Camp 4 at Abruzzi route our summit push towards K2 summit. I was feeling great for my planned summit without use of supplemental oxygen. So I was advancing very well, overtaking many people until being directly behind the rope fixing team. Unfortunately, shortly before the start of the bottleneck at around 8300m, the rope fixing team stopped their work and turned around. So we were all forced to turn around. I was very frustrated and disappointed as I was feeling great and the night was overall good for a summit push, with ok temperatures and little wind. But if the risk for fixing the bottleneck is too great (due to avalanche danger, hip deep snow and a big crevasse), there is unfortunately not much to do.

So we turned around, went back to Camp 4 at Abruzzi, slept there, and then I managed to take off with the paraglider from Camp 4 at around 8000m to fly down to basecamp. I believe this is the first time someone has actually flown from K2 :). (There was also another paraglider to fly down that day.)

Am I going to do another try in the next days / weeks? No. The past days have shown me again what I dislike about 8000m climbing: No climbing challenges, you are ultra slow, and most important: You are about 80% dependent on other people, variables, weather, things totally outside of your control.

The longer version:

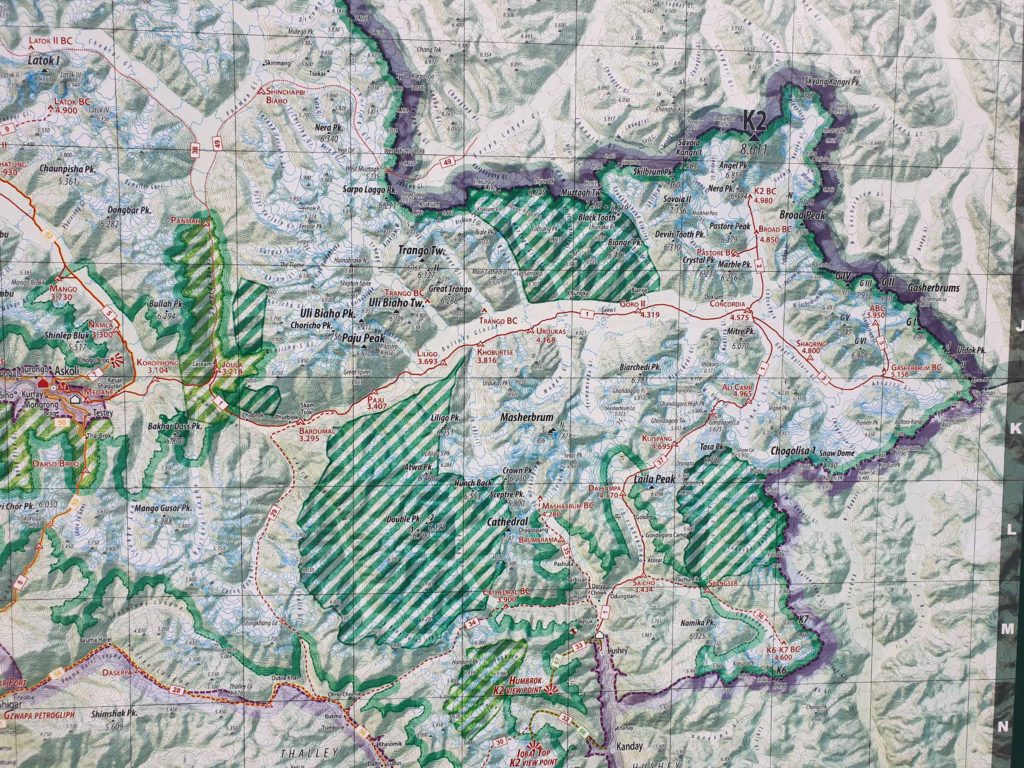

Max, Nima Dorje Sherpa and I had started up the Cesen route as it is more direct than the Abruzzi. Unfortunately, conditions turned out quite challenging, as there was much more fresh snow than forecasted. So the trail breaking was very hard. We went directly to Camp 2 at around 6200m on Sunday. Also, there was almost no one on this route, so the trail breaking was entirely up to us.

The route is indeed steep and sustained, so it is very physical, more so with snow.

On Monday, we then mounted to Camp 3 at around 7000m. Unfortunately set up lower than we had hoped. And again a very physical day.

On Tuesday we then had a very long day, going from Camp 3 at 7000m to Camp 4 on the so called shoulder at around 8000m. There were about 40cm of fresh snow and the trail breaking was very exhausting and annoying. So we arrived quite tired at Camp 4.

Then the next disappointment. Unfortunately, the rope fixing team had not yet even managed to fix through the bottleneck. Apparently, an avalanche had swept down the brave Sherpas doing the fixing, during which unfortunately one broke an arm, and ripping apart the work done so far.

Ok, so an unplanned night at 8000m without supplemental oxygen. Not good.

The next day, that is, Wednesday, I made the proposal to follow the rope fixing team directly, during the day, when it is nice and warm. Well, this sounded good only until we watched then the rope fixing team and could see that they were very slow, obviously due to bad conditions – but so it was clear that they would definitely not reach the summit during the day.

Now another problem arose: We had borrowed a tent from another team, but their members would arrive in the day. So we had no tent to wait for until the night, when possibly another rope fixing attempt might start. Thus, we had no choice to actually walk down to Camp 4 on Abruzzi route where our other sub-team was. Let me tell you, it is very annoying to actually lose altitude meters on an 8000m peak…

But as mentioned, no choice.

So we went down to Camp 4 at the Abruzzi route and spent the afternoon there to hopefully start a summit push.

And word was: Yes, the rope fixing team will surely start in the afternoon and surely fix to the summit!

So we started our summit push with one day delay yesterday Wednesday 17 July at 8 pm! I was very motivated and felt really good for my planned no-O2 summit push! I had started quite at the end of the „queue“ but soon overtook most people, walking in my own speed, as slowly as possible – the summit is the goal!

Things looked and felt good until shortly before the bottleneck. And then, unfortunately and frustratingly the rope fixing team again had to turn around due to too great a danger due to avalanche risk, hip deep snow in the bottleneck, and a big crevasse (my understanding).

You can imagine that I was deeply disappointed, frustrated, sad and annoyed. But alas, these brave Sherpas only turn around for good reason, so not much to be done.

We turned around then (as all other teams, e.g. from Seven Summit Treks) and went back to Camp 4 on the Abruzzi route. After an ok night I got up quite early and prepared the takeoff with the paraglider. Thanks to David for helping / holding the glider!

And, after the disappointment with the failed summit push, at least I managed an excellent takeoff from 8000m and then had a great flight from K2 directly to Basecamp :). To my knowledge the first ever paragliding flights from K2! Video follows…

What about other teams or more attempts? To my understanding, the team from Madison Mountaineering is right now at Camp 4 of the Cesen route and might check out the situation for a summit push tonight. The Sherpas from Seven Summits Trek might also do another try in a few days after some rest. Other than that, I only know of Adrian Ballinger and his team who spent one night at Camp 4 and will probably now weigh his options for a summit push in the next days.

What does this overall mean for me?

I am not going to do another attempt in the next days or weeks, even if other teams try again (although the situation at bottleneck will probably stay dangerous). The reason is that I simply do not want to do this stuff anymore.

The past days have again shown that you are at an 8000m peak, more so at a high one like K2, extremely dependent on the actions of other people and teams, on conditions, on weather. This is the opposite of autonomy and what I normally prefer. Sure, you can climb alone without support from other teams, Sherpas, fixed ropes etc, but then your success chances are even more minimal.

So in the end I have to answer the question what else I could do with my time instead of waiting at basecamp, hoping for the rope fixing team to have success, hoping for good weather etc.

I mean, how much would I progress for example in my climbing if I took off four weeks and just went climbing?

So, when doing this weighting I have come to the conclusion the balance for 8000m climbing is now off and I feel I should devote my time to other things. By the way, I had come to this conclusion already during our unplanned night at Camp 4 at 8000m.

Thus, no, I will not wait for another possible summit window and I will not try again, I want to come home now and do active stuff where I am in control of most variables :).

Still, here some pictures from our summit push!

Starting the Summit Push from Basecamp!

Starting the Summit Push from Basecamp!

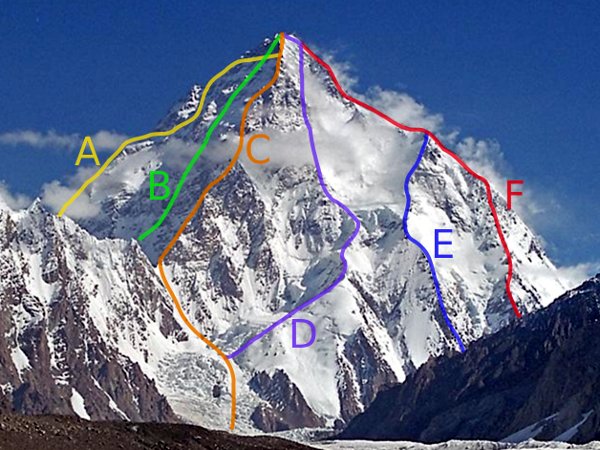

The Cesen route from below. Start on the right snow field and then continue mostly along the ridge.

In front of the Cesen route

On the way to Camp 2

On the way to Camp 2

Passing Camp 1

On the way to Camp 2

Camp 2

Camp 2

Starting away from Camp 2

Starting away from Camp 2

On the way to Camp 3

On the way to Camp 3

On the way to Camp 3

On the way to Camp 3

On the way to Camp 3

On the way to Camp 3

On the way to Camp 3

On the way to Camp 3

Lower Camp 3

Upper Camp 3

Upper Camp 3

Upper Camp 3

Camp 3 7000m

On the way to Camp 4 8000m

On the way to Camp 4 8000m

On the way to Camp 4 8000m

On the way to Camp 4 8000m

On the way to Camp 4 8000m – Bottleneck visible

The famous bottleneck – huge seracs!

The famous bottleneck – huge seracs!

The famous bottleneck – huge seracs in full view!

On the way to Camp 4 at Abruzzi

On the way to Camp 4 at Abruzzi

Abruzzi Camp 4

Abruzzi Camp 4

Starting the summit push in the night at Abruzzi Camp 4

The menacing bottleneck and its huge seracs in the night

Turnaround decision 🙁

Back in Basecamp – disappointed, but that is fate at K2

And here now the video of the spectacular flight from K2 in beautiful and fantastic Pakistan / Gilgit-Baltistan :)! I managed to takeoff from Camp 4 on the Abruzzi route at approximately 8000m. Probably these flights are a premiere, that is, I am probably among the first people ever to fly from K2. Enjoy!

Big thanks again to Ralf Reiter from www.airsthetik.com for the wing and the support!

And for your viewing pleasure: A short video from me on my trial day as a Sherpa 😉 at Broad Peak, arriving at Camp 3 at 7000m: Carrying a 200m rope in addition to the big backpack makes you tired! And the Sherpas usually carry two or three of these ropes!